On a Path of Beautiful Destruction

Jel Suarez talks about her art of deconstructing and decontextualizing found materials and recalls the experiences she’s gathered in her journey, connecting what seems to figure in a creative path she was meant to take all along

By Patti Sunio

It’s impossible to pinpoint a specific road map or a structured process that led Jel Suarez to where she is now. Instead, “everything just flows,” as the 30-year-old self-taught visual artist puts it. “When I started, there was really no intention of making art,” she says. “I just kept on doing, creating. There was really no turning point in which I decided, I'm going to make art.”

Suarez’s art requires deconstructing found materials: cutting, manipulating, pasting, and piecing together objects, texts, and images into a collage, allowing the decontextualized pieces to form a new narrative. “Once I start cutting, it just flows,” she explains of collage-making, her first medium, which begins with gathering and collecting, seeking objects at thrift shops, or pulling out things from her personal collection.

“My instinct to sort, organize, and arrange kicks in,” she adds, “and I just like to play and experiment and see where it goes. The objects I gather give me an idea of what I can build.”

Her creative process is organic and continuous. “It's not something that I plan or think about, with a step-by-step process,” she explains. “For me, I just happen to enjoy exploring materials and what can be done with them.”

It could very well be a practice born out of childhood curiosity. She recalls her early influences from random memories and mentions her grandmother’s vast collection of books in their family home in Parañaque, which she was forbidden to touch as a young girl. “I think that maybe led me to grow up wondering,” she shares, “why wasn’t I allowed to go through my grandma’s books?”

Instead of drawing or painting, Suarez finds more connection in random objects she can hold, touch, and inspect

INFLUENCES AND INSPIRATION

Growing up, Suarez was curious about a lot of things. She was also interested in architecture, but her parents thought it might not lead her to a profitable profession. She took up psychology in college instead, which led her to further studies on special education. A fond memory from her practicum brings Suarez to a time she spent with children with special needs, where she found herself observing the way they worked. “I noticed the repetitive patterns, and with tasks like cutting, for example, they were quite perfectionists,” she recalls. “In a way, I could relate that to how I make art—it’s repetitive, but the action is not intentional.”

Studying while working as a preschool teacher turned out to be quite a handful, and this led Suarez to explore life outside the academe. She found herself going out with friends who were active in the local art and music scene, introducing her to an exploration of self-expression. “I used to think of art as just paintings, or artists creating from nothing, with a blank canvas,” she shares. “But frequenting galleries allowed me to see new mediums of art.”

Japanese surplus shops, book stores, and thrift shops were Suarez's early playgrounds. Without the formalities of art-making, she instinctively picked up objects wherever she went, collected things, and made them into something new

From the decoupage art on pen holders she made as a child, to sticking random objects on stones and rocks she’s found and gathered, to the collage works she’s created out of the sheer joy of cutting and pasting, Suarez was used to making little projects for herself. It was during the early era of Instagram when she decided to post her works for the world to see, and friends urged her to join exhibits to further showcase her craft.

Looking back, having no formal art training allowed Suarez to explore as she pleased and draw inspiration from the various fields of studies she’s immersed herself in. The more she practiced and worked, the more she discovered her style and the identity of her art. Fully committing herself to her craft, Suarez eventually left her teaching job and focused on shows and commissions. Her work grew from there. “It was only when I started exhibiting that I thought of ways to make my work more archival and exhibitive,” she shares.

From collage art, Suarez ventured into assemblage, object-making, and, more recently, paper-making. Her plans of settling down in Bacolod had been pushed back due to the lockdown, which left her stuck in the city. And because she didn’t have anything with her—save for one luggage and a few stones in her bag—Suarez decided to make her own paper, to have material to put her collage on. Thankfully, a few surplus shops remained open despite the pandemic, where she uncovered old Japanese boxes for teaware and other delicate ceramics. "I was drawn to them because they were made so intricately," she says.

"Untitled (Playing Set)" is one of Suarez's recent works for Parcel Exhibitions; one of her portable works for Golden Cargo Gallery, collage on handmade papers and stones in a wooden box

The experience led her to make portable art, works that can be folded and tucked away, or put into neat little boxes and brought on travels. “Where I'm staying now is a shared space, so I don't really have a huge space to work in,” she shares. “And whenever I work, I would need to tidy up the space after. I realized it's a good practice to clean up every time after I work, because when I get back to it, I start refreshed.”

THE ART OF LETTING GO

Suarez has always been one to collect things—from stickers to stationery, to stones and books. “I realized I can be quite thoughtful when it comes to objects,” she confesses. “I start with collecting for myself, which means that I am drawn to the material and have a certain attachment to it. I appreciate the intimacy of objects, the emotions attached to things.”

Friends from high school have also grown an appreciation of—and attachment to—her work. They have kept some of her work from years back, which she had given them as tokens. One was a book she made with acetate sheets, with cutouts pasted on each page. It forms a whole picture when the book is closed. “I didn't intend for them to be artworks, but more like a gesture to express my feelings.”

One of Suarez's favorite works is an accordion book she made, which can be seen in the video. While it can be folded into a compact object when not displayed, it took up a huge space at the gallery. “I am also drawn to video work. I think emotions are easier communicated through videos.”

Ultimately, the practice of art-making has taught Suarez to let go—she’s had to let go of works she’s spent so much time on. “I think the practice has also helped me compartmentalize things,” she shares. “Maybe there's a lot going on in my head and my work is one of the ways I sort through them.”

Suarez doesn’t measure a show’s success based on whether her pieces were sold out, or if the event was well-attended. “Because when you gauge your output based on other people,” she reasons, “what do you get from that? Where is your ‘self’ in your work?” She values, instead, her growth from the experience, what she’s learned from the time and emotions she’s invested.

The past year certainly made room for a lot of growth. “It feels great to see how much my work takes up so much space on display, knowing the behind-the-scenes, that I made them all on a small desk," she shares with a chuckle. “I like when I'm able to push myself to explore new mediums, new ways of art-making, and not just settle on making collage art. I'm proud of how my work has evolved.”

WEAVING STORIES

Having realized that artistic expression can be more than just paintings and that her own medium can change, Suarez believes that contemporary art is “continuously evolving.” “Our design influences can be a hybrid of many different things, thus we interpret it in unique ways that can be difficult to capture in just one description.” She concludes, “Filipino art can be anything.”

But there’s a common thread in how Filipinos make art, Suarez notes. “What binds us is the predisposition to experiment with the natural materials available to us, such as tropical woods, fiber and grass weaves, rattan, and bamboo.” Before the pandemic, Suarez herself had been travelling around the country, collecting objects she finds unique in the places she visits. “Maybe it's because of our climate,” she adds, “but these materials are also very adaptable, and so it offers makers plenty of ways to manipulate and create with them.”

An assemblage on tsuitate. Suarez is currently preparing for an upcoming solo show for The Drawing Room Gallery in November, which she is keen to dive into once she flies back to Bacolod

Suarez also notes the “rhythmic patterns” that tend to result in the use of natural materials. “From the textiles in clothing to the weaves in furniture, I feel our Filipino products are more 'breathable' in a sense—lightweight and delicate.”

But perhaps even more importantly, what also binds Filipino artisans, craftsmen, and makers is storytelling. From the pieces they create, Filipinos are able to tell stories that reflect everyday lives, and for Suarez, it's a natural tendency. “We have a penchant for expressing our life experiences in a way that integrates all the influences and traits that make us whole and unique.”

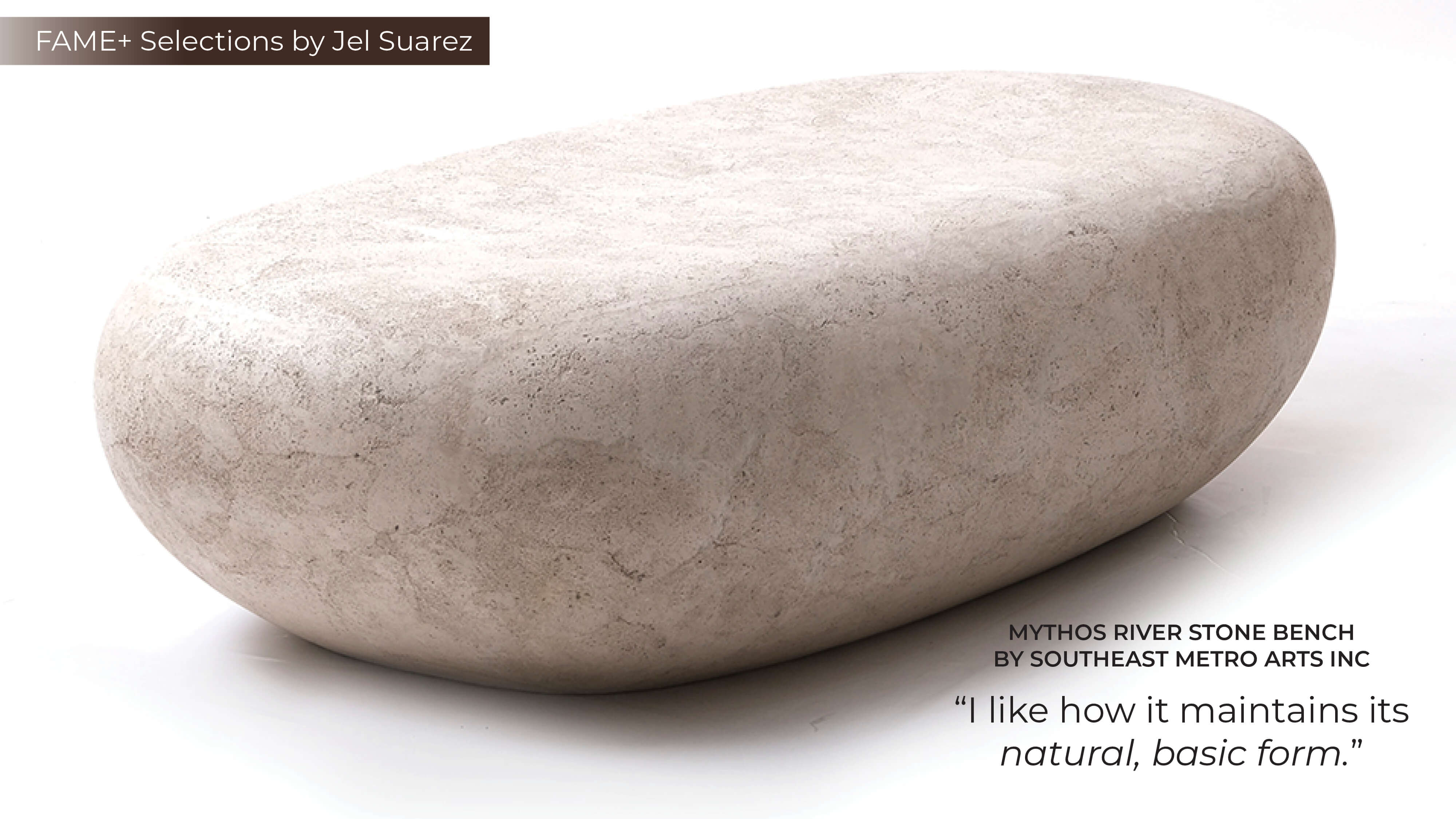

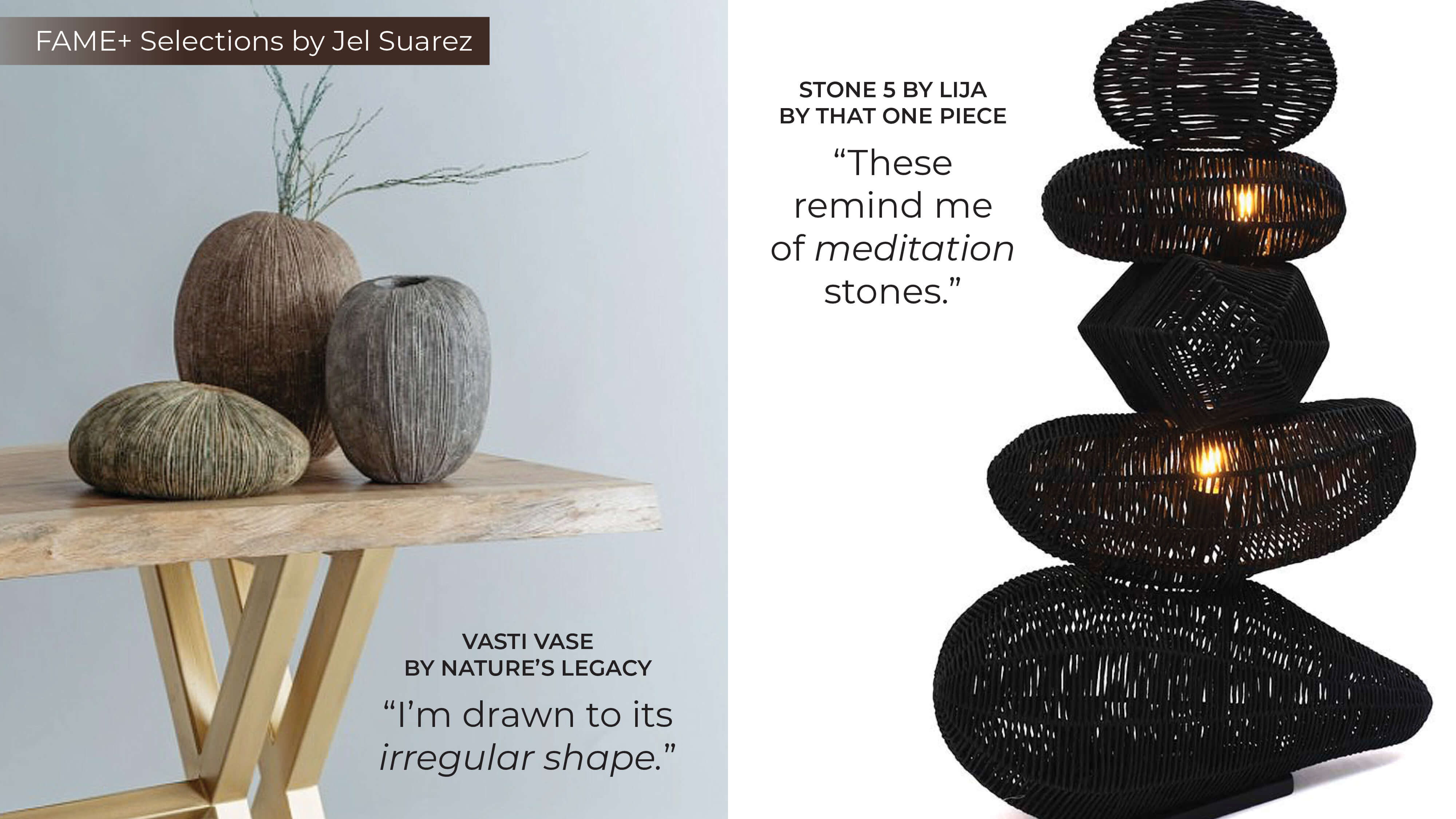

FAME+ Selections by Jel Suarez

Many of the Filipino homes we grew up in tend to be filled with trinkets and things, and can be very expressive, notes Suarez. On the contrary, she prefers bare spaces that are free of clutter, and this stone bench, according to her, "feels very Zen."

Suarez is naturally drawn to works that mirror her aesthetic, such as these Nature’s Legacy Vasti Vases and Stone 5 Floor Lamp by LIJA by That One Piece. They give her a glimpse into how else she can expand and improve her craft.

A follower of the brand, Suarez likes that E Murio's pieces can be multi-functional. “The baul feels architectural, but also like an abstract work. I can imagine the many ways I'll be able to use this.”

Video by Rog Castillo II for West Gallery; photos courtesy of Jel Suarez

.jpg)