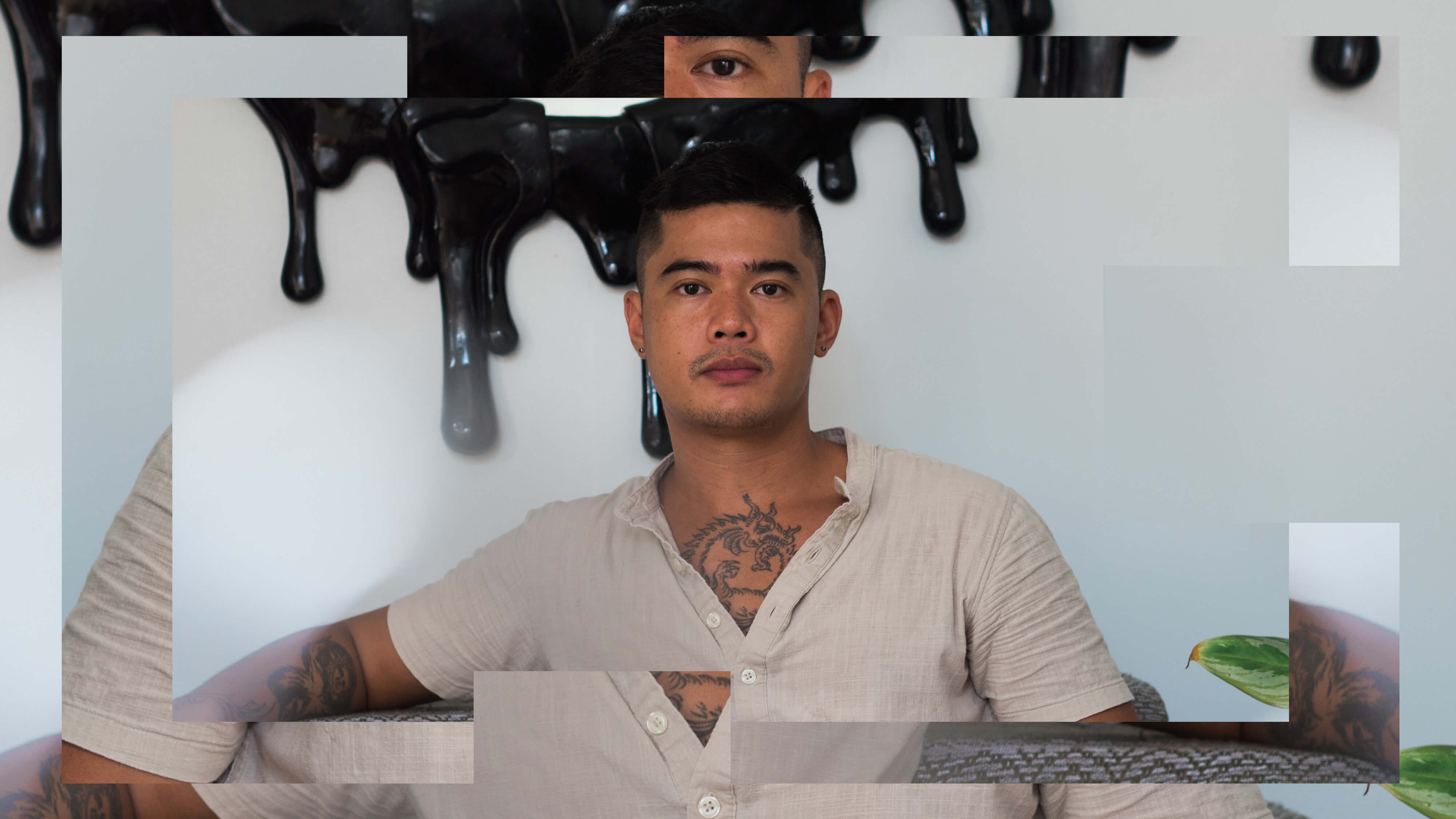

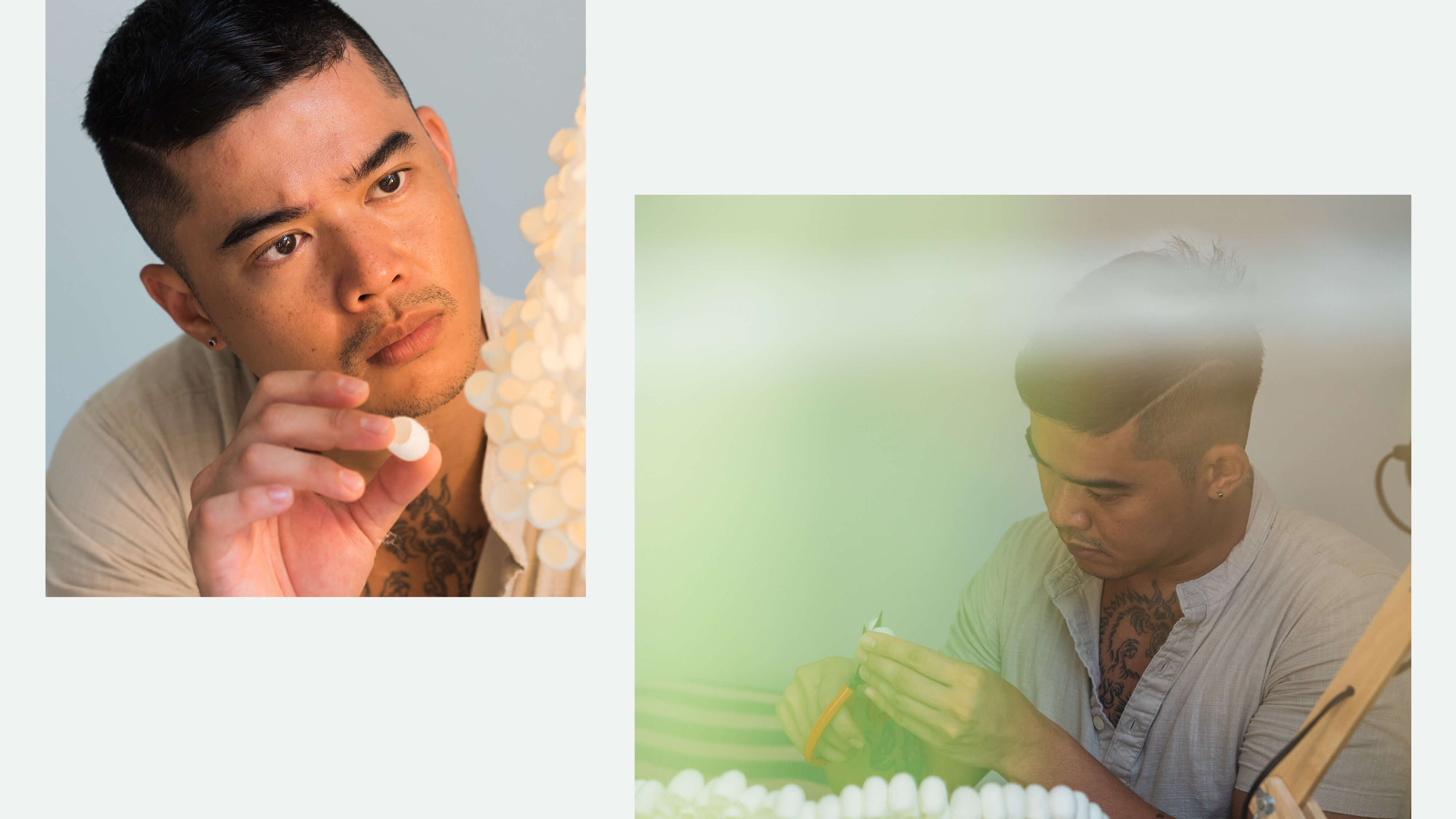

Inside the Mind of Leeroy New

In public spaces and outer space, the relationship between the structural systems and his large-scale structures—plus, what’s new for New

by Patti Sunio

Leeroy New was introduced to the world of art in the form of sci-fi, fantasy, and horror movies. “When I was young, I saw creativity in those things. I didn’t see these creatures as scary, as something strange or evil or monstrous. I always waited for the aliens and monsters to appear because I thought, wow, this is art. In my mind, I didn’t know it yet, but these are products of creativity,” says New.

Born and raised in General Santos City, New was surrounded by traditional works of art—paintings, drawings, sculptures. “All I ever thought was that art was related to the more traditional forms,” he shares. “I had very limited access to contemporary art-making practices back in the ’90s, before the internet. Our libraries had very limited content about art, too, so I had to be creative in sourcing them out. I’d look at illustrated books, card games, comic books, films, TV shows.”

New eventually left his hometown after being accepted into the Philippine High School for the Arts in Mt. Makiling, Los Baños, Laguna. “That’s where all my preconceptions on what art is changed,” he reveals. A far cry from the art he was used to seeing as a child, his mentors in high school were engaged in installation art, found objects art, large-scale kinetic sculptures, among others. “For me, it was exciting. In my mind, at that time—in my very impressionable, young probinsyano (‘from the province’) mind—I thought: art could be anything.”

“My journey from General Santos to Philippine High School for the Arts kind of predetermined everything that I do now. Because there [in my high school], I studied with theater and performance artists, musicians, and creative writers, so there was a kind of a holistic framework,” explains New. “And after that, I just went wild.”

“There was no one point where I realized, ‘Ah, I want to do art,’” says Leeroy New. “I was one of those kids who just used drawing or visual arts as a form of play and I never really got over it. It just evolved to the next thing and the next thing and the next thing…”

New’s training in art school allowed him to easily transition from one mode to another, from production design and theater work, to filmmaking and fashion. Originally trained as a sculptor, New has gone beyond the walls of traditional art-making, and there’s no telling where he’ll take his craft next. “From something very traditional that merely depicts something, to becoming a vehicle for change, we’re problematizing harnessed creative practice as a means for real, practical, social, and environmental change.”

OUTSIDE SCHOOL AND INTO PUBLIC SPACES

New would gravitate towards art-making in public spaces, creating large-scale installations that allude to the otherworldly creatures and structures that filled up his imagination as a child. There was no limit to where he’d take his art—and where his art would take him.

“Initially we were problematizing, as art students, the infectivity or inefficiencies of existing art systems. Like the gallery and museum system, we’re all aware that these were adapted concepts from our colonizers or the global powers, so they may not necessarily be effective culturally in the Philippines,” he points out. “And so in the process of exploring more effective ways to show our art, one of them was deciding to use the public space.”

Setting up in public spaces brings to light many questions—from who gets to determine which spaces can be used by the public, to who decides how it’ll look and be designed. “It’s a very complicated subject and topic and still, a lot of our city woes are from poor infrastructure planning. The design is very anti-people. So these are all systems that affect us and I think creative designers and artists really have to join in coming up with ways to address these issues. These are kind of like big ideas but… definitely worth getting into and fighting for,” says New.

He recalls the Bakawan Floating Island Project, which he made in 2016, in collaboration with urban designer Julia Nebrija, which was intended to help restore and rehabilitate the Pasig River, Manila’s main waterway that has been declared biologically dead. Through art on the water, the project hoped to resuscitate the relationship between the Pasig River and its people. The project was partially funded by the Burning Man Global Arts Program.

Giving “creative identity” to these spaces not only brings attention to the place and how else it can be developed. It likewise invites a change in perception on how these spaces can be used and the ideas that the public can get from it. Ultimately, according to New, “it can help form habits of the community.”

And the bigger the platform, the bigger the responsibility. “As an artist, you learn to be more aware of all these things that contribute to these spaces,” he says in hindsight. “You should be aware of your role, that you’re not one savior coming in, you’re just one of the many people who are stakeholders in these spaces and contribute in the best way you can. You learn a lot from people, you’re not just working with people from the arts and design scene, you're working for everyone who uses these spaces. You learn to see different perspectives, think in systems.”

“There’s only so much you can do by focusing on just one thing,” New shares. “To begin with, that’s what I realized at once. I’m only helping so many people if I sit in my studio and work on precious art objects to show in the gallery that only few people can see.”

For New, finding purpose in your practice invites a paradigm shift in thinking about art. “Which community do you want to be part of, help change, or serve? Are you making art to adhere to a particular system of art production or do you want to help contribute to its evolution and change?” he asks. “These are the existential questions you have to grapple with in the beginning. And then after that, it’s easy.”

TRANSFORMING TRASH TO TREASURE

Part of New’s training as an artist and designer is taking pretty much anything, from discarded materials to plastic waste, or, literally, trash—and turning this into a piece that can serve a new purpose. “Whatever we put our minds to, whatever it is, we can find a way to absorb this waste and turn it into something else, be it a livelihood, into art, a design object, or even something practical,” he says. “We know how to problem solve using existing materials and steering them toward the direction that we want, function-wise and design-wise.”

At the onset of the pandemic, the world was on lockdown and access to resources was limited. “As a creative, I had to decide quickly the direction I would go into. So I took it on as a challenge to implement a circular economy by using waste produced by communities, like discarded furniture, appliances, plastic bottles, other waste materials,” New shares.

When it comes to materials, New knows no bounds, having worked with a variety of materials from wire (in earlier collaborations, creating lamps) to resin (such as in his flaming Sacred Hearts), to indigenous materials such as abaca and bamboo, (as seen in his ‘spaceship’ for the Paoay Sand Dunes of the Northern Philippines), and even industrial pipes and cable ties (primarily used in his Balete Series). “That is something I want to explore in the future, create like a kind of materials library,” he adds.

And so creating from what’s existing, be it trash, scraps, or whatever can be found at present, comes naturally for New, as evidenced in the extraterrestrial-looking, wearable head gears made from plastic containers and bottles that he’s become known for.

“It’s a global phenomenon. People are starting to teach themselves how to think differently and move toward a direction that is beneficial to the entire global system,” New observes. “The theme for the Biennale of Sydney next year is ‘River,’ which has to do with weather, the community, and the environment. And upon invitation to the show, they proposed that I use discarded surfboards for my little installation.”

New is currently building his Burning Man installation in La Union, the Philippines’ surftown up north. “It’s an installation slash inhabitable structure slash pavilion,” New shares. “A section of it will display the agricultural systems of the place, and a huge chunk of it will be made out of surplus materials and discards. A portion of it will be designed in partnership with local artisans and craftsmen, harnessing local techniques of craft production here.”

On the Filipino creatives’ enduring spirit, New says: “We’ve learned to offset the seeming scarcity that we have, which I think we don’t actually have, because I think we’re a very rich country with resources that have been historically mismanaged or stifled by other powers. Generally, we are a culture that’s prone to resourcefulness, creative production, and humor. And this is something I try to harness—this very resourceful nature that we have and our inclination to celebrate concepts of abundance and nature and all that.”

ART AS RELIGION

There’s no slowing down New, whose friends describe him as an “energizer bunny.” In the past months, he has been shuttling back and forth his base in Manila and in La Union, where he is building his Burning Man installation.

Setting foot in La Union has encouraged him to “slow down,” so to speak. “In La Union, the pace is different. We’ve been trained working for so long in Manila and you realize you’re capable of doing so many things efficiently,” he shares. “But being outside of Manila also teaches you that’s not necessarily the best or the right way to work. You can just take the tasks that are sufficient. You don’t have to overwork yourself. The values that have been imposed on us in the context of Manila progress and growth—all of it is also just a construct,” he adds.

Other than keeping the plants in his room healthy and working on relatively “smaller” projects with friends, New is also preparing for a project with the Somerset House in the U.K., a showcase at the Hawaii Triennial next year, the Busan Art Festival, as well as an expo showcase in Dubai, among many other things. “There are uncertainties, so these are all planning and hoping for the best,” he says.

Still, there’s no watering down his spirit. Artists living in the Philippines in the middle of the ongoing pandemic are continuously plagued with many challenges, but New is one who welcomes the challenge of traversing difficult terrains—literally and figuratively—and making the best from it. “I guess I’m lucky that I’m able to pick myself up most of the time and continue,” he shares. “Because I truly am interested in the work that I do. It’s not something I do to escape. I enjoy it, and it fuels me to do more.”

“Art is prayer,” concludes New, and for the artist, it’s become his way of responding to the world. “Somehow, I’ve replaced religiosity with my dedication to my craft. Creativity is a good lens to view the world with,” he muses. “My creative practice is my ritual that guides me with how I move in the world. It helps me continue creating in these difficult times.”

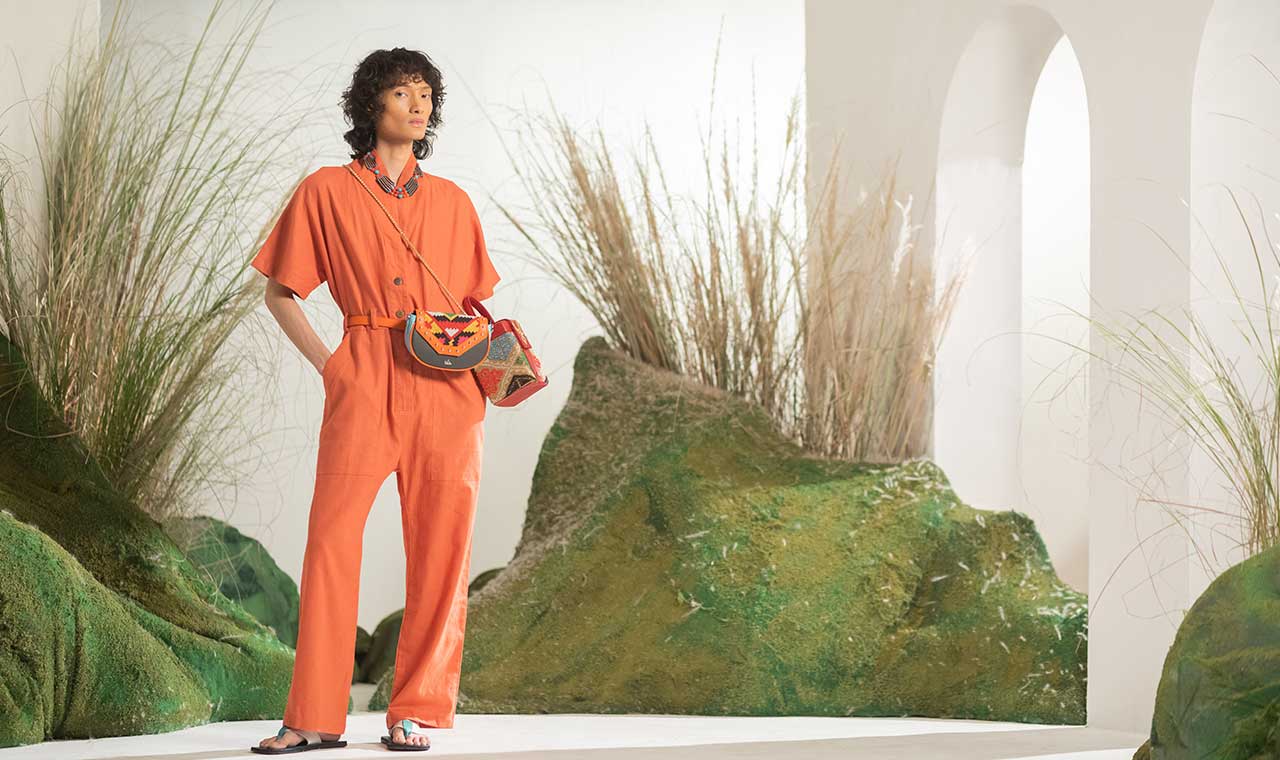

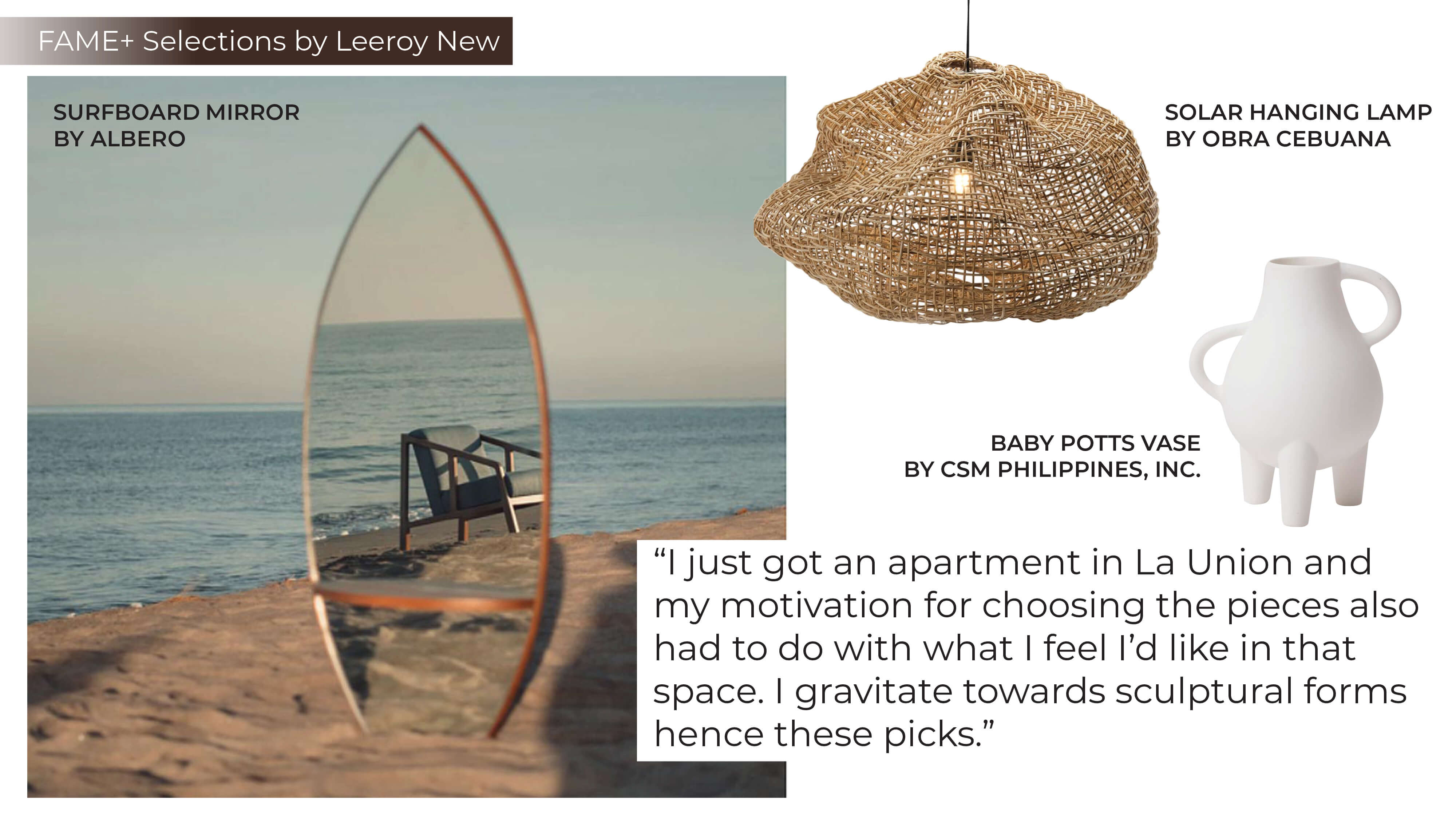

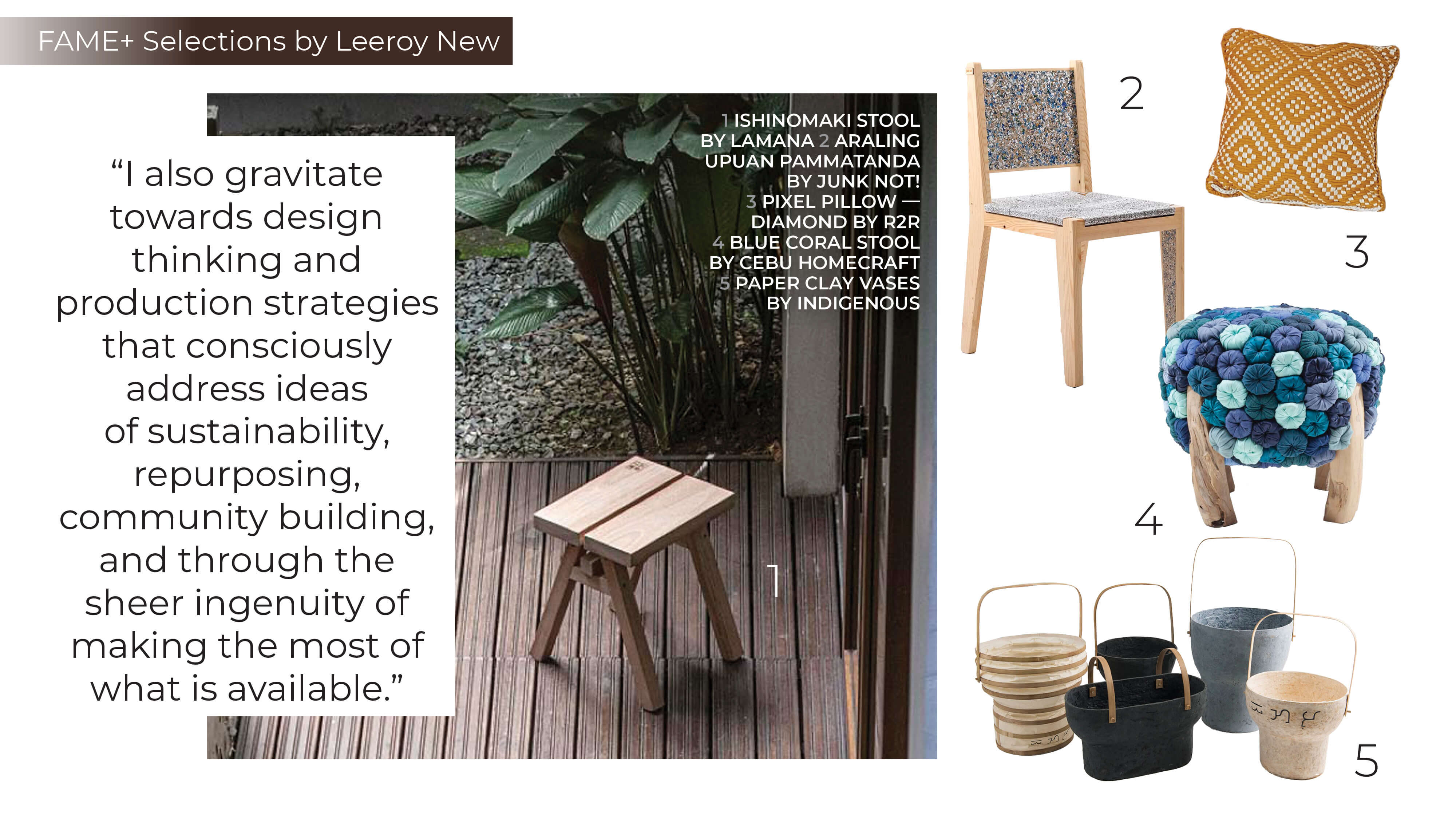

FAME+ SELECTIONS BY LEEROY NEW

Photography Arturo Dedace III