Building Brands, Building Communities

At the heart of fair trade practices are efforts that involve partner communities on a deeper level. NIñOFRANCO and Junk Not! share how their initiatives greatly benefit everyone involved, makers and consumers alike

by Joy Celine Asto

Climate change and the pressing issue on ethical production practices have long been concerns in industries such as fashion, home, and lifestyle. Thankfully, makers and consumers alike have become more open in joining the conversation and gaining more awareness about it.

After years of consuming things with very little thought given to where they come from and where they’ll go after use, changing our ways can be difficult—but making the first step is key. While shifts don’t happen overnight, small and consistent efforts can make a difference, slowly but surely. A guiding principle from the World Fair Trade Organization puts the goal into perspective: what we aim to sustain are business models that put the people and the planet first.

TouchPoint speaks to two homegrown brands, NIñOFRANCO and Junk Not!, who have committed to such efforts, proving that making clothes and producing furniture can be done through conscious means and fair practices.

IT STARTS WITH A VISION

Fashion wasn’t the first love of Davao City-based Wilson Limon, who originally wanted to be a doctor. His decision to switch careers proved to be fortuitous, though: it led him to establish NIñOFRANCO, a ready-to-wear line that reinvents the traditional Bagobo Tagabawa garment, the rich textile-making traditions of the Blaan, Mandaya, and Tagakaulo people.

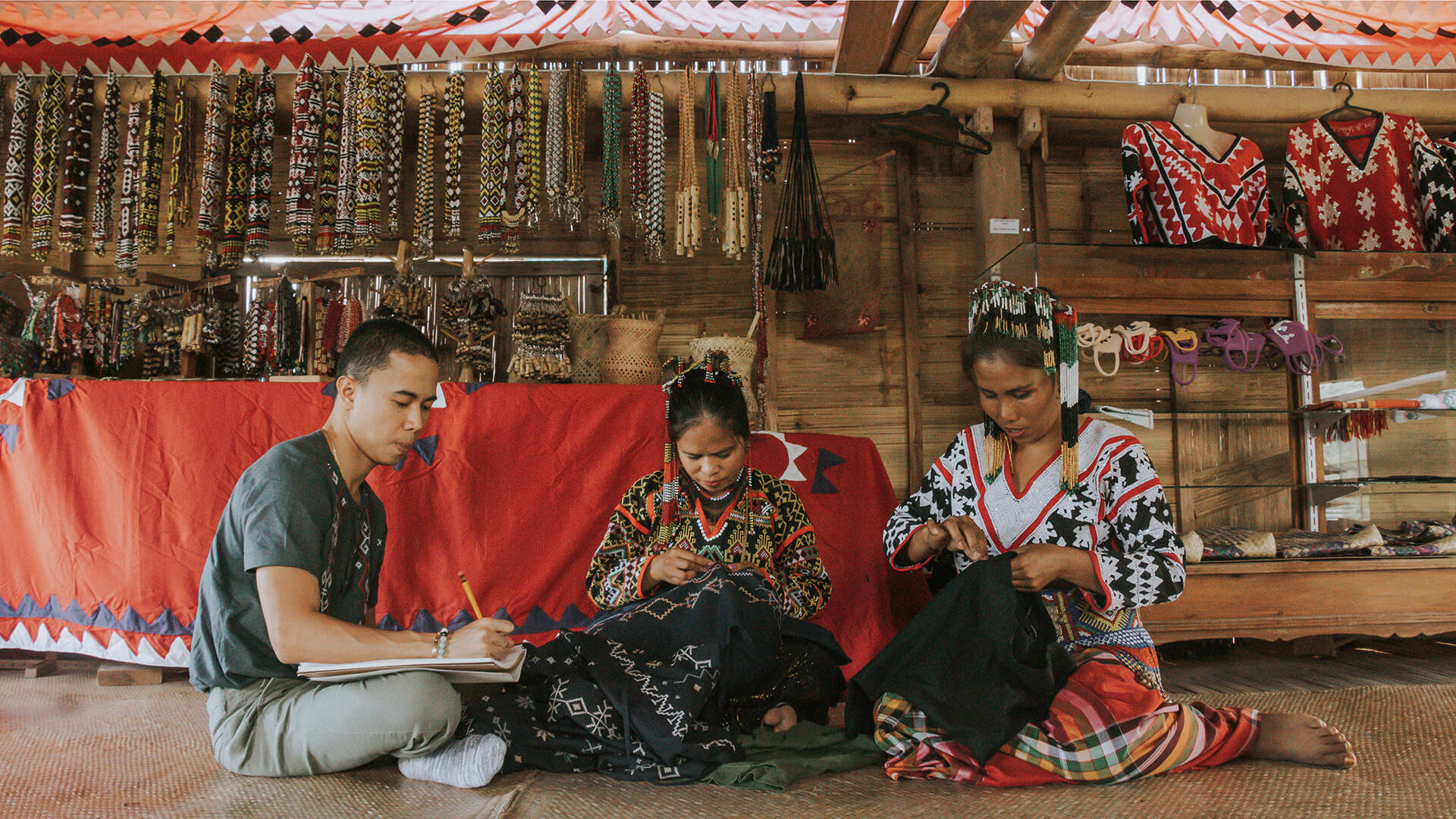

What began as Limon’s fashion design thesis turned into an inspiring journey that allowed him to re-learn his culture and work closely with various communities. As the brand’s creative director, Limon saw the potential of fusing local craftsmanship and contemporary fashion. “I wanted to modernize traditional craftsmanship to make it more relatable to the market and, in the process, also empower women artisans through our collaborations,” he begins.

“Our goal is to transform a Western-minded Philippines into a culturally enriched nation that gives livelihood to individuals and communities who safe-keep the true art of the Philippines,” Limon says of the vision behind his fashion brand. “With this in mind, NIñOFRANCO builds and fosters creative partnerships with ethnolinguistic groups, mainly in the Mindanao region, and has become a leading brand in creating contemporary ethnic pieces that are uniquely Filipino and Mindanaoan.”

Biñan-based interior designer Wilhelmina Garcia started her social enterprise Junk Not! designing bags, but eventually turned to furniture and interior design after creating her first chairs in 2013—all while focusing her effort on finding ways to create with the least waste possible.

“Junk Not! envisions itself to be the leading design firm that champions environmental stewardship in achieving a sustainable community,” she shares. “We want to transform communities by finding innovative ways to recover all waste materials and upcycle them to high-end furniture and other home decor pieces—while providing sustainable livelihood.”

NEXT STEP: COMMUNITY BUILDING

In working in close partnerships with communities, there are many factors to consider behind the scenes. As partner communities get involved in the design and production process, it must be reiterated that they also understand the rationale behind the work and the reason behind the processes. They also need to be informed and involved on all levels of production so as to retain their craft’s authenticity. These communities are the heart of the brand, after all.

Getting to know each of the partner communities very well is vital for NIñOFRANCO. It is the only way for them to deeply understand the communities’ ways and traditions, and establish a strong collaboration. Their joining of hands with the Tagakaolo tribe in Sarangani in 2018, for one, was sealed with a formal ritual of partnership with the leaders of the tribe. “It was a prayer ritual asking for Tyumanem’s (God’s) guidance in our collaboration with their community,” shares Limon.

“Fair trade, for me, is about how you build a good relationship with the community that you work with, when you are able to establish a healthy collaborative work,” he points out. This means a community engagement that is based on transparency, where there is clear and open communication on the terms of the collaboration. More importantly, it’s essential that the weavers understand how their roles are significant in NIñOFRANCO’s mission. Beyond embroidery and textile-making, they play a huge part in honoring their heritage and preserving weaving traditions.

“Another example of fair trade that we do in NIñOFRANCO is giving autonomy to our partner communities in setting their production and artisanal fees,” he reveals. “We do not have control over their prices. In return, we only ask for the exclusivity of the designs we have created together.”

He ensures that customers and the public fully understand what goes behind the scenes through transparency in their features and advertisements. “Here at NIñOFRANCO, we always give credit to our partner communitie,” Limon explains. “We only provide them with our vision and creative direction, but the execution is 100% by them.”

It's no easy task partnering with multiple communities. NIñOFRANCO creative director Wilson Limon points out how one must study the story and significance behind the designs, the patterns, and ensure that these are appropriately applied to the clothing

There are many misconceptions surrounding fair trade practices, one of which is that this benefits the community more, rather than the enterprise, Junk Not!'s Wilhelmina Garcia points out. But she argues that it all depends on how the founder practices fair trade

Garcia also reiterates how collaborations must go beyond simply producing the goods; community involvement plays a big role, too. Working with communities who reside near Taal Lake, Garcia realized that the residents were contributing to the pollution. She sought to engage them in becoming stewards of the environment and taught them to collect, clean, and prepare the plastic waste, which she then uses as raw material for her designs.

Garcia recalls a time when, instead of going through their usual process of collecting plastic waste and cleaning them to be used as materials for the furniture, the weavers resorted to buying plastic (to make into twines) in order to speed up the process. With such shortcuts, the values and the purpose of the enterprise are lost. This is why Junk Not! keeps an open discussion with the community to remind them why they do what they do for the brand, and why some things have to be avoided. “It takes only one of them to do something that isn’t aligned with our values to affect the entire production line,” stresses Garcia. “I also had to learn to handle situations like that to help them better understand the program, that it’s not just about making a profit; we also have to balance it with the environmental and social impact.”

It takes a lot of work to ensure that she and her collaborators see eye to eye, and these efforts are necessary for the partnerships to be fruitful. “As most of the weavers are housewives, I know they have a lot of chores and responsibilities, too, so I respect their time,” says Garcia. “I let them take part in the production in their spare time. I also make sure they’re compensated well, but within a certain quality control. Their outputs also aren’t quota-based. As a result, they make better use of their time and do something productive.”

NIñOFRANCO’s Wilson Limon was inspired by the rich culture and weaving traditions that surrounded him in his hometown. Rather than having these weaves only in formal and national attires, he sought ways to incorporate them into modern casual wear, and, in the process, introduce new ways of how our weaves can be worn

Since utilizing plastic packaging to turn into fashion and furniture pieces isn't easy to do, Junk Not!'s Wilhelmina Garcia had to first learn and master the techniques herself, before showing the community how to do it. The process of standardizing processes was challenging to implement but it is a way to streamline the process with her collaborators. “After designing and conceptualizing comes the weaving part,” she says. “I do the prototype first. Then, I teach a weaver on the kind of weaving I want, especially if it’s an experimental style. The succeeding production is then done by my weaving team.”

GOING THE EXTRA MILE

Fair trade businesses are not centered on profit, but are guided by principles that uphold just compensation and ethical treatment of producers. These allow social entrepreneurs like Limon and Garcia to pave the way for more lasting benefits for their partner communities.

“We aim to sustain the livelihood and preserve the artisanal craftsmanship of the tribes we work with by incorporating their embellishments on our modern pieces,” says Limon. Through NIñOFRANCO's different projects, the women artisans from tribes are given a platform to create and show their works and be acknowledged for their craft.

"We gather resources for the children’s school supplies and assess the kind of opportunity and livelihood programs that can be given to the women of the communities," adds Limon. Last year, at the height of the pandemic, NIñOFRANCO also started #MaskofHope, a collection of face masks featuring different indigenous patterns, in order to continue supporting the livelihoods of its partner communities.

Likewise, Garcia set up a profit-sharing system that her partners can use as a community fund. “My relationship with them doesn’t end with the compensation they receive, which I know runs out quickly,” she reveals. “The community fund is there for the community’s emergency use.”

An example would be Garcia’s pilot project during the Taal Volcano eruption. “There were donations that time, but I wasn’t able to do fundraising because I got sick because of the sulfur,” she shares. “But I was able to use the community funds to provide them with kitchen supplies to use in evacuation centers instead of plastic cups and utensils.”

Garcia also actively involves her clients with her initiatives, such as with her Trash Innovation and Exchange for UPcycling (TIE UP) project, where old furniture is given new life through Junk Not!’s upcycling methods. Having observed that most big corporations’ solutions simply involve donating the plastic waste as their contribution to saving the environment, Garcia decided to change that through TIE UP. “They cannot just make me a dumpsite; they should be part of the process,” she notes. “This circular approach became my challenge to the companies since they’re the biggest producers of waste. Instead of bashing them, why not create a program that will benefit both parties and solve the waste problem?”

This approach, Garcia points out, is also a way for customers to keep their plastic consumption in check, with the goal of minimizing the amount of plastic they consume. “Through this, I want to make customers realize that by buying from us, they also make an impact in the environment. Whenever they buy a chair from us, they also get a computation of how much plastic we have saved and prevented from ending up in the oceans. Customers also get a 15% discount if they collect the plastics themselves, which in turn we use to make the chair that they’re ordering.”

Some advocates of this movement perceive social enterprise and fair trade as two sides of the same coin. While the former is a mission-led model, the latter is focused on providing better prices, working conditions, and opportunities for workers and communities. Social enterprises give fair trade businesses a sense of purpose, while fair trade practices serve as a foundation on which social enterprises can operate.

This synergy is the driving force behind the sustainability efforts of brands like Junk Not!. “I think that being a social enterprise will solve a lot of social problems, if only more multinational companies will lean toward sustainability,” says Garcia. “I also think that collaborating with social enterprises is a good jump-off point for these big businesses to get into fair trade practices. If they can only use their platforms now to solve social issues, we can be heroes of our own survival. That’s really my only wish, that there will be more social entrepreneurs to help bridge that gap.”

NIñOFRANCO’s creative partnerships yield one-of-a-kind pieces that celebrate Mindanaoan heritage as well as provide the tribes with a steady source of income. These pieces are modern and can be easily incorporated into everyday wear

Junk Not! literally makes treasures out of trash. Other than refurbishing old furniture, they churn out collections made of materials that would otherwise be thrown in dumpsites or polluting the seas. According to Junk Not!, “Denim and plastic are two of the most durable materials on the planet today, and among the highest polluters.”

THE BETTER IMPACT

Behind brands like NIn?OFRANCO and Junk Not! is the goal to make a lasting impact within and through the communities they partner with. As Limon points out, it comes with respect for the people and the intention to preserve and further make known the traditions of these ethno-linguistic groups. “We must understand that relationships with people are more important than the business that we plan to establish,” he says.

Garcia also adds that measuring the impact of a social enterprise is also very effective in communicating the benefits and advantages of fair trade. “When you assess your business with this impact, it’s very effective compared to looking only at the impact on profit. It makes a big difference on how you and other businesses will see your enterprise. Also, most green consumers are now looking for the story behind your business. Fair trade practices serve as a good guide for that.”

“If you have a goal in mind to really help the community and not just yourself, this measurement of your enterprise will be very fulfilling,” Garcia notes. “But if your target is for your own benefit, it will not be an effective practice for you.”

Photos courtesy of the brands