The Art of Philippine Embroidery

In delicate designs embossed to perfection, these embroidered pieces go beyond showcasing the beauty of handmade. They represent years of tradition and highlight the patterns and figures inspired by stories and dreams and the intricate art sewn together by skilled hands and passionate hearts

by Patti Sunio

The Philippines abounds with skilled embroiderers. To name a few, there are the Itneg embroiderers from Abra; the artisans from Lumban, Laguna, known for their work on the traditional barong Tagalog; and in Mindanao, the Mandalas from Davao and T’bolis from Lake Sebu. As rich as the archipelago is in resources and inspiration, so are the passion of our artisans and the Filipino brands that bring to the fore the centuries-old techniques in hopes to preserve and nurture the art of embroidery.

TouchPoint speaks with five FAME+ brands who have utilized a variety of embroidery techniques in their own unique ways, proving that with skills honed through years of practice and artisans who continue to keep the craft alive, there are endless possibilities to proudly showcase our embroidered masterpieces.

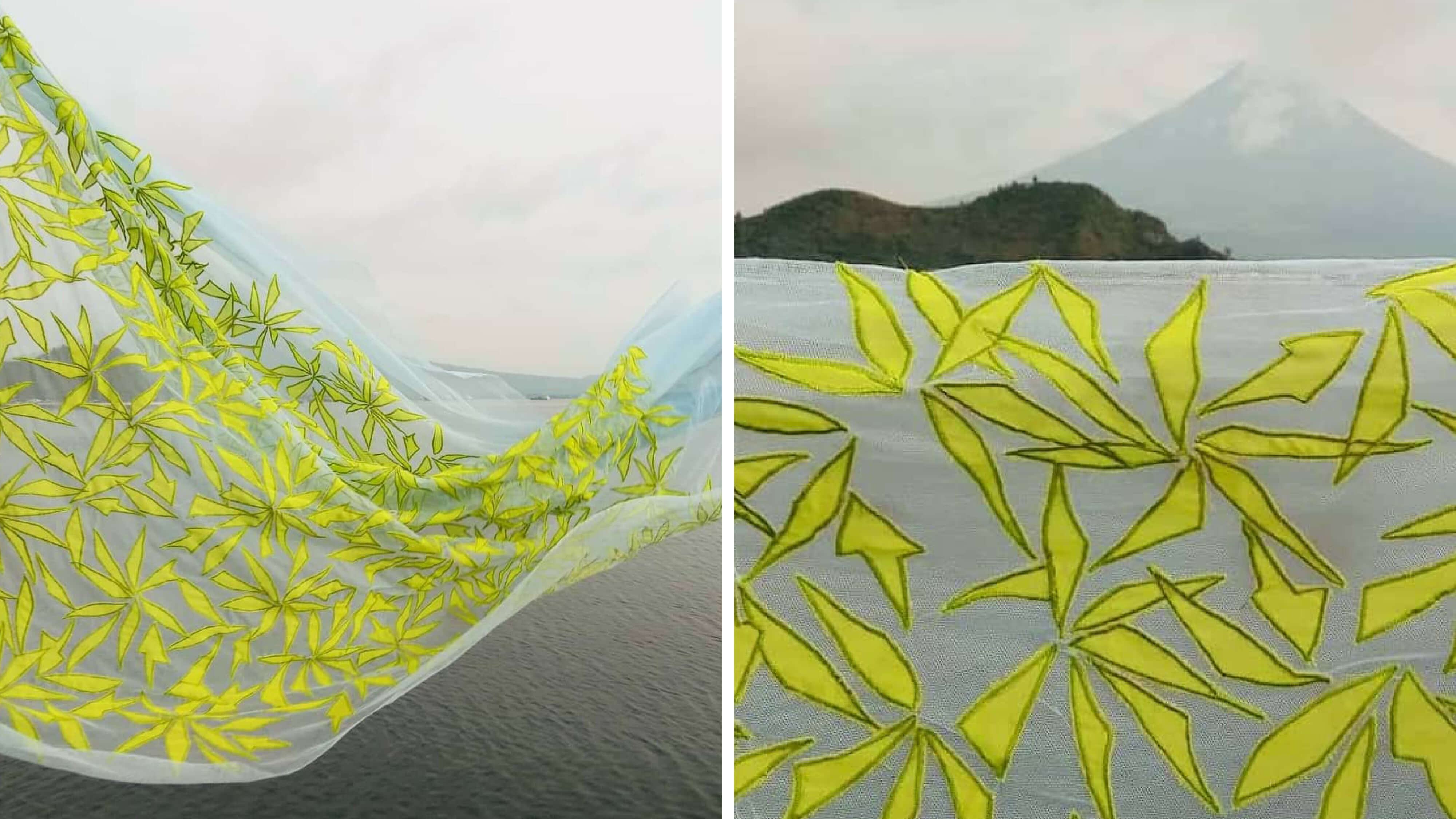

AMARIE

“I feel that, recently, in the Philippines, there has been a sort of a cultural awakening and a revival of everything indigenous and artisanal,” begins Anne Marie Saguil, creative director of luxury resort wear brand AMARIE. “There are many beautiful types of embroidery being done all over the world, but the embroidery we do here has its own distinct feel and aesthetic. I think it is just a matter of celebrating what is ours and working creatively to further develop and improve what has already been handed down to us.”

“When a piece has been worked on lovingly for days, the artisan somehow imparts their soul and personality into it,” says Saguil, who works with local communities of at least 40 to 50 embroidery artisans, to produce embroidered pieces that take from a week to a full month to finish. “When you buy and wear a piece that has been worked on skillfully by the hand, you can feel its vibrancy and dimensionality. When properly done, these pieces achieve a rich luxurious quality and can also be passed on to next generations.”

AMARIE collaborates with embroidery artisans from Taal and Lumban, as well as in T’boli and Abra. “Both Taal and Lumban embroidery are the same in technique and style. They use fine delicate strokes which allow the artisans to achieve more fluid designs such as curved vines and flowers,” says Saguil. “These artisans use a bastidor or the instrument that keeps fabric flat and taut so as to embroider their fine delicate designs.”

“The T’boli tribe in Lake Sebu’s embroidery is more of a fine cross stitch technique which can achieve elaborate and intricate patterns that are more geometric in style and nature,” she adds. “In Abra, the prevalent type of embroidery has bigger strokes with thicker threads and also more graphic in style.”

One of the brand’s first designs was women’s work and casual wear inspired by the traditional men’s barong. It resulted in modern-style barongs of vibrant colors, some combined with denim, others with linen, detailed with unexpected colors of barong embroidery.

To date, AMARIE’s designs have evolved from using the traditional barong pattern. “Since AMARIE is a resortwear line, you will see our embroidery embellished in more casual easy looks such as beach cover-ups, casual day dresses and coordinates, as well as occasion dresses for beach and garden events,” says Saguil.

IDYLLIC SUMMERS

“For Idyllic Summers, our embroideries on the surface are designed to be beautiful, but what lies beneath is our purpose of wanting to carry on age-old traditions of handmade and our heritage as Filipinos into the modern day, and more importantly, supporting the valuable artisans behind these special crafts,” shares Idyllic Summers founder Steffi Cua.

“We focus on the process of handmade embroideries and needlework, similar to luxury fashion houses and haute couture ateliers,” she adds. “Apart from our natural bias that handmade is aesthetically superior, we are also adamant about keeping our culture and traditions alive by supporting the Filipino artisans and indigenous communities behind these valuable skills.”

A breath of fresh air, Idyllic Summers’ pieces are timeless yet rooted in heritage. In of-the-moment hues and versatile, summer-ready silhouettes, inscribed in its pieces are beautiful embroidery that tells our rich history.

“We personally don’t believe embroidery is a ‘trend’ as it has stood the test of time—imagine, dating back to 30,000 B.C.!—and will probably outlast us, provided it is given channels to survive,” Cua points out. “The history and traditions attached to our embroideries are what make it distinctive from the rest of the world. It isn’t merely a craft for us, embroidery is stitched into our culture and identity as Filipinos.”

While embroidery has been in our culture for centuries, and have made experts out of our artisans, Cua admits that the local industry needs “more time, investment, and support” if it were to prosper and be as distinctive as its counterparts in other countries, such as India and France, two countries that are “synonymous to haute couture embroidery and exporting the trade.”

“The Philippines can be known for its skilled artisans, but our embroidery at the moment needs a vehicle to communicate it, and we think it’s in the form of ready-made resortwear,” she says. “If you strip away all preconceptions and think about traditional embroidery as it is, which is purely a method of surface design, the contemporary applications are boundless. The different elements of fashion design, such as line, shape, textile, color, and texture can be applied to create something more aspirational and approachable for today’s environment.”

Idyllic Summers works with four different community groups of embroiderers. The Ylang Ylang dress makes use of the bobbin lace technique in the form of flowers tediously woven by the women of Sta. Barbara in Iloilo (seen in photo), who are part of a livelihood project composed of about 20 women artisans who are very skilled at creating bobbin laces, a type of needlework that originates from the 16th century, taught to them by a Belgian missionary. The bobbin lace flower is then positioned on a bed of linen, where it is stitched in place. Then the linen backing is cut out to reveal a sheer haze of floral lace on bare skin.

The embroidery on the Rositas collection utilizes several bullion stitches in various lengths and sizes to create small roses (as seen in photo). It is a method of twisting thread around a sewing needle several times before inserting back into the cloth. These are made by women in the Visayas region who were trained by Europeans during the clothing manufacturing boom in the Philippines in the ’80s. These women maintained their embroidery work, while foreign manufacturers have left the country for cheaper alternatives like Vietnam and China.

The brand’s Diamantes pieces are hand-embellished by two women, Jenizel and Myla, from the T’boli tribe in Lake Sebu, and they use locally sourced mother-of-pearl sequins also found in their tribe’s traditional dress. The diamond pattern is stitched in conjunction with other geometries and repeated to create the contemporary Diamantes design.

Currently in development are patchwork embroidery sewn by the women of the Panay Bukidnon tribe in Calinog, who have historically adorned their traditional attires with complex running stitches and colorful patchwork embroidery. “We have married their needlepoint florals called ‘bulaklak ng labog’ and reinterpreted them in their girigiti patchwork method,” shares Cua.

KELVIN MORALES

“For me, embroidery is a reflection of our rich culture and history,” says fashion designer Kelvin Morales. “It is part of our Philippine heritage and it tells of our time and history because the modernization and transition to computerized embroidery has involved changes in the embroidery process, making it more commercial and affordable. And with this in mind, I think we need to focus more on preserving our handmade embroidery practice. I believe it will help to represent our Filipino craftsmanship globally.”

For Morales, the art of embroidery is one that Filipinos can own and excel in if we focus on the continuous innovation of our designs and embroidery skills. “Our embroiderers learn from experience and passion. One fully embroidered barong takes about one to four days to complete, depending on the design.”

Known for his unexpected, experimental, and contemporary approach to design, Morales makes use of embroidered details to add an element of surprise to his pieces. “Embroidery is very flexible in the sense that it’s easy to tweak or transform, just by changing the design and color,” he explains. “In this way, one can use embroidered details to adapt to the modernizations in clothes, trends, and fashion.”

Kelvin Morales likens the art of embroidery to painting. “It is one of the most expensive techniques used in clothing, as it requires a lot of time and labor. It’s almost the same process as with completing a painting—but instead of paint, we use threads and a needle.”

“For our brand, we use a manual, hand-guided embroidery machine. We focus on the color contrasts that each element makes to make it more realistic, as if using thread as a paint brush with different strokes, texture, and color dimensions popping out,” says the designer.

TWINKLE FERRAREN

“What’s fun about embroidery is you get to play with textures and designs and the different colors and thicknesses of thread,” begins experimental fashion designer Twinkle Ferrraren. “The beauty is that a lot of our natural fibers can be used as the ‘thread’ for embroidery. It gives a piece of clothing this handmade touch and feel and adds a unique characteristic. Behind this piece is the work of human hands, a story, a tradition, a passion, a design, and an art. All these are incorporated into the piece that you are wearing,” she adds.

Exploring the limitless possibilities one can do with embroidery, Ferraren has utilized the craft in a variety of wearable pieces as well as decor for the home: from swimwear to resort wear, with bikinis and sarongs featuring embroidery, as well as shirts, pants, and other fashion accessories, to a home decor line that includes pillows, curtain trims, seat covers, table cloths, and napkins. “I would like to think and believe that anything art and handmade will always live on. The characteristics and the technique with what you can do with your hands is endless,” she points out.

Although Ferraren recognizes that the craft needs more support as “everything is switching to man-made and machinery and the mindset is always being ‘more more more and fast fast fast,’” she remains hopeful. “It will take continuous education, awareness of the process of the art form and passionate individuals who will continue to support the artists and designers utilizing this art form.”

Of the brand’s recent collection, Twinkle Ferraren makes use of at least seven embroidery techniques. These are: 1) hand embroidery, which uses lots of types of stitches, from flat type to embossed type, to running stitch, back stitch, and chain stitch; 2) outline embroidery; 3) patchwork embroidery, or the joining of several pieces of fabrics together; 4) applique, which is more known as a patchwork technique, joining pieces of fabric over another, and sometimes incorporating other materials such as beads, stones, or sequins; 5) candenete or a continuous chain-type embroidery that adds instant texture on a fabric; 6) callado, which is one of the most intricate forms of embroidery usually done on handwoven piña silk, a traditional style of whitework embroidery that our country specializes in; and 7) suksuk or the embroidery done in handwoven textiles, where the patterns, motif, and designs are incorporated during the weaving process.

The designer works with artisan communities in Lumban, Laguna, as well as in Bulacan. These embroidery artisans have learned of the art through their mothers and grandmothers. “Apparently, the community in Bulacan is the same place where my grandmother used to go… and I didn't even know this!” shares Ferraren. “Only until I was thick in my design world that my mom told me that she remembered my grandmother going there, saying ‘diyan ka pala nag-mana’ (you got it from your grandmother).”

WEAR YOUR CULTURE

“Wear Your Culture (WYC) was created from our passion to keep the cultures and traditions of Filipinos alive,” shares Alvin Degamo, president and founder of WYC. “During one of our travels, we discovered the talent of the Manobos who do hand embroidery. We learned that it is a dying tradition and it is too good to just let it die.”

“Nobody wants to learn embroidery because nobody uses them or buys them,” he explains. In response, the WYC team set off to explore ways in which the traditional embroidery techniques can be incorporated into modern-style clothes and accessories. “As you can see, Filipino artists know how to use colors together and their works are clean and seamless—it’s a real art,” Degamo points out. “It is in this way that the products become more appealing to the youth. We hope to increase the demand for hand embroidery, as well as show the young Manobos the need to continue this tradition.”

“In ancient Manobo culture, wisdom learned through experience is expressed through the oral traditions of tod-om and gudgud,” explains Degamo. “While the tod-om originates from the babaylan’s (high priestess) own words, the gudgud springs from the incantations of invisible abyan, or spirit guides. Living close to the land and becoming intimate with the natural elements, many of the Manobos’ seemingly utilitarian practices possess a spiritual dimension. Such is the practice of the traditional Manobo embroidery—the vanishing art of suyam.”

“What makes an embroidered piece extra special is the story attached to it—it’s personal or specific to a tribe,” Degamo concludes. “That’s the extra value and that’s what makes a piece of it worth handing over to the next generation. It’s done by hand. It’s an interpretation of a dream. It helps a community.”

Wear Your Culture primarily works with the Manobos, who have learned of the craft passed on by their elders. To date, the brand works with a community of about five embroiderers. “They are still expanding by letting the young ones try one section of a design at a time,” shares Degamo.

In addition, Degamo and his team also work with the adopted mothers of the Carmelite Sisters of the Sacred Heart in Davao City, who learned of the craft through training given to them by the sisters. There are about ten embroiderers working on one project at a time. In addition to nurturing the craft, these mothers are able to send their children to school as a result of their embroidery work.

“The WYC Accent Pillow with Eagle Manobo started from a Manobo dream of an eagle hovering over an untouched mountain in Agusan Del Sur,” explains Degamo. “The Manobo embroiderer interpreted it to be his grandfather, the protector of the mountain who passed on and came back as an eagle who continues to watch over the mountain. She now wants to pass on this protection to the homes of the new owners of our Manobo Eagle Accent Pillow.”

Photos and videos courtesy of brands

Video editing Kit Singson

(1).jpg)